Best Scenes of 2019

Every year we watch hundreds of films that contain thousands of scenes within them, and through it all, we come away with a handful of stand out moments. These are the scenes we think about walking home or discussing with our friends at dinner. They contain the one liners, the gut punches, the tear-inducing, pull on your heartstrings, make you cry and you don’t know why moments that leave lasting impressions on us for days or even weeks at a time. Whether it be a climatic revelation, a subtle moment of directorial brilliance, or a poignant punctuation to conclude a film, these scenes display a creative, technical, and thematic mastery that we simply can’t stop thinking about. As selected by our writing team, these are our favorite scenes of 2019.

Major spoilers for the films below.

Parasite

A Letter to a Father

After what may go down in cinema history as one of the harrowing birthday party scenes of all time, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite has one more gift to us – a coda. We find that Ki-jeong has died, leaving her brother Ki-Woo and mother, Chung Sook ,to face fraud charges alone. Their father, Ki-Taek, is missing and wanted for the murder of Mr. Park. Destitute, Ki-Woo finds himself aimlessly returning to the (former) Park home repeatedly until one day he notices a Morse-code message in the light fixtures that he interprets to be from his father, trapped in the Park’s hidden basement. In the span of a couple minutes, we are led through a dreamlike montage of Ki-Woo dedicating himself to becoming successful, buying the Park home and reuniting with his father. Heartbreakingly, we suddenly depart from the montage in the last shot of the film to find this sequence was, indeed, just a projection of Ki-Woo’s fantasy. He remains in his family’s dilapidated basement, his father trapped miles away in the Parks hidden basement.

“I did think that it was necessary to be honest” Bong has discussed in interviews, “If I just end this film on an optimistic note, if I'm too easy about it, then I thought that would actually even make the audience even angrier." While the climax of Parasite is unquestionably the birthday party sequence, Ki-Woo’s letter to his father is the final pinch of salt in the wound. Much has been said about Parasite’s commentary on economic inequality, but Bong chooses to end his film on a portrait of economic immobility. Ki-woo is not going to earn enough money to buy the Park home. He is not going to free his father from the hidden basement to live out their lives monetarily carefree. Almost all the odds point to Ki-Woo remaining in the same economic stratum as he started, even the very same basement. When we first meet the Kim family, all they had was each other. The final realistic garnish of Parasite is having the surviving members of the Kim family lose even that camaraderie. As the credits begin to roll, Ki-Woo’s letter to his father is the lasting taste in the mouth of the audience as they leave the theater from one of the best films and endings of 2019.

-Kevin Conner

Uncut Gems

“Let’s fucking bet on this.”

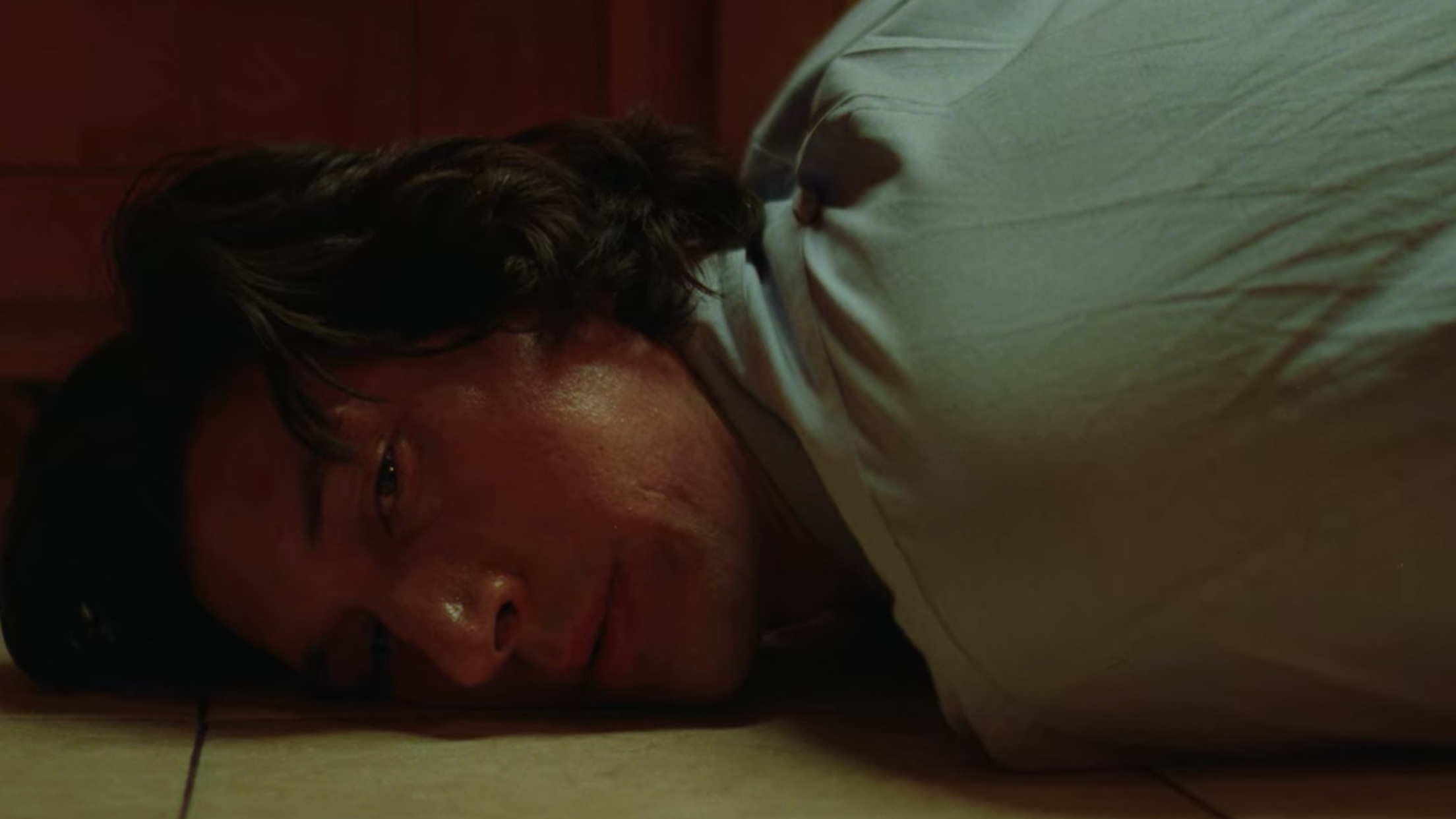

Just when you thought Howard Ratner was in the clear, he doubles down. For the last hour and thirty minutes of the Safdie Brothers’ Uncut Gems, we’ve seen Howard engage in deal after deal to free himself from a long over due debt, and when he finally comes up with the money to buy his freedom, we think he might have actually changed. That somehow between the all his bullshit and the skin of teeth he actually managed to come out of this ordeal alive and he can return to his normal life. But that’s not how Howard wins.

When Kevin Garnett enters his office with $155,000 in cash to buy the Ethiopian black opal Howard has been peddling around town the entire film, he is essentially given a ticket to end all his troubles. But before he leaves, Garnett frustratingly asks why he’s doing this? Why give him the run around? Why do circular deals when he originally offered to buy it way back in act one? Because Howard wants it all. His response could be summarized as a rallying cry for people who are doubted time and again, but want so badly to prove their worth. Garnett wins in basketball, but this is how Howard wins: by taking all his newfound earnings and placing a three-way parlay on Game 7 of the Eastern Conference Finals. “Let’s fucking bet on this,” he says and your jaw hits the floor, stunned that a man with the keys to his freedom would so flippantly jeopardize them.

What ensures is an immaculately constructed symphony of stomach sinking stress that hinges on Howard’s confidence in the game and the knowing reality that he can’t come out of this clean. While debt collector Arno and his crew remain locked in the two-way security entrance, growing angrier and angrier, breathing down his neck, all you can do is sit and wait for the final outcome to play out, but as the minutes dwindle down and the final component of Howard’s parlay falls in place, you realize that he hit it big, really big.

That $155,000 initial bet netted him a $1,225,000 payout, fulfilling the dream he’s been chasing since we embarked on this crazy journey in New York City’s Diamond District. The tension eases. With all the money he could ever need to cover his debt, Howard celebrates, releases the locked door, and BANG. He’s shot right in the face. The calming aura felt throughout the theater is suddenly and unexpectedly contracted into a tiny bullet hole beneath Howard’s left eye as you jump back in your seat at the unexpected nature of it all. Despite pulling off one of the most unbelievable gambles in sporting history and proving his worth, the mobsters he kept at bay weren’t having it, and Howard is finally punished for all his actions.

What makes this scene so great comes in two parts: the remarkable escalation and diffusion of tension by the Safdies, and the finale of Howard’s arc. Those ‘This is how I win’ memes are a godsend, but it’s also the singular line where you realize who Howard is and why he’s doing this. He wants to make it big and he’s doing it the only way he knows how. The lavish American Dream lures him into the American way of winning — lying, cheating, and conning his way to the top. That pursuit ultimately kills Howard, but we can’t help but relate to his desires of monetary excess in a capitalistic society. Though, if Howard’s tale is any warning, the greed we all share may one day get us killed.

-Greg Arietta

John Wick 3: Parabellum

Knife Museum

The third installment of the action-filled John Wick saga picks up immediately where it left off without skipping a beat. Scores of assassins descend on John’s (Keanu Reeves) location after excommunicate orders go into effect, and while attempting to flee, he stumbles upon an antique arsenal full of explosives, guns, and blades. After a heart-pounding attempt to load and fire a pistol — a nod toThe Good, the Bad, and the Ugly — he launches into close quarters combat with a trio of ferocious adversaries.

Director Chad Stahelski grounds his fight sequences with flashes of realism that ultimately work to heighten the absurdity. In a breakdown of Parabellum’s fight sequences, Stahelski explains how he wanted to have a “snowball fight” with knives. Instead of landing a perfect, fatal strike every time, most of the knives ricochet and scatter to the floor. As deadly as John is, he’s still a mortal man with a realistic hit rate. But consequentially, the ones that do stick make a serious impact and raise the stakes. With the seemingly bottomless smash-and-grab ammunition, the flurry of blades back and forth verges onto slapstick for the audience. Stahelski combines his expertise for kinetic action with a playfulness that makes the most of a playground full of weaponry.

In a film that is wall to wall with the best set pieces of the year (dog stunts, horse stunts, and “boxing with bullets”), it’s hard to pick one favorite, but the knife museum is emblematic of the tactical competence and creative attitude driving the film.

-Megan Bernovich

The Last Black Man in San Francisco

Mont’s Play

Hearing a truth is a tough pill to swallow. For Jimmie Fails, it means acknowledging his grandfather’s house is no longer his. So stuck in the past is Jimmie that it takes the help of his best friend Mont to move him. Played quietly by one Johnathan Majors, Mont doesn’t have much to say. He is a withdrawn, he is subtle, and he is thoughtful. What few words he does speak carry great weight, and when we arrive at his climatic play, we receive a powerful sermon on the back of an outstanding performance.

For the entire film, Mont has been silently working away on a play based on the events around him. When he finally cracks the finale, he and Jimmie are on the verge of being forcefully removed from the aforementioned San Francisco house they’ve been squatting in. So on their last day, they hold a one-night-only showing of Mont’s hard work for their friends, family, and neighbors.

Speaking louder than we’ve ever heard him, Mont begins by depicting the death of his friend Kofi from earlier in the film. His death brought by his overt masculinity and conformity to the environment that denied a tender touch when it was needed. He was put into a box as Mont says, unable to break free from factors he let define him. Then the examination shifts to Jimmie, as Mont cites his inability to move past a house he has held onto for so many years. “People aren’t one thing… You exist beyond these walls,” he proclaims. Louder and louder he drills Jimmie until he confronts him with the reality his grandfather didn’t build the house they’re standing in.

It’s a forceful moment, one characterized by the bite of a repressed truth. You can’t help but feel as if Mont is shaking the whole house with his words, a departure from Mont’s stoic nature that signals the necessity for him to do so as Johnathan Majors delivers a boisterous performance that sells the immediacy of this revelation. All you hear are Mont’s words and Jimmie’s deflection, but by the end of the scene, you are left in deafening silence knowing that Jimmie Fails is moving on.

-Greg Arietta

Marriage Story

Knife Trick

Writer-director Noah Baumbach goes to great lengths to show just how flesh and blood the characters truly are in Marriage Story. As his divorce and custody battle rages, Charlie (Adam Driver) is pressed to allow a child protective services evaluator (Martha Kelly) to observe his parenting. After what has already been an unimpressive evening, Charlie shows the evaluator a trick with a keychain knife where he pretends to cut himself, while actually slicing his arm.

In an intricate actorly drama, the moment gives Adam Driver a chance to prove his comedy chops. We squirm as things cascade from bad to worse, stricken yet laughing at the farce of it all. Martha Kelly’s quiet deer-in-the-headlights bit is what sells it, as she watches his catastrophic failure to hold together any chance he had of winning sole custody of his son. It’s a perfect microcosm of his emotional experience of the divorce; he plays off undeniable pain and suffering as everyone witnesses. Repeatedly insisting he’s fine, Charlie attempts to hide his personal shortcomings as poorly as he conceals the blood dripping down his arm.

Amidst the film’s shifting perspectives between its two leads to balance the sympathy between them, this scene both effectively aligns the viewer with Charlie while admitting that he is, at this point, acting out of selfishness. His son’s best interests have been sidelined in a competition between the estranged parents, and as Charlie collapses to the kitchen floor, it becomes apparent all is lost.

-Megan Bernovich

Little Women

Christmas at the March’s

Often the sure sign of a great director comes in the form of great nuance. While there is merit to scenes of grandeur, it’s just as challenging if not more so to make everyday events compelling. In Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, the writer director does that for the entire film.

You could choose from any number of scenes that are exemplary feats of this notion—Jo and Beth on the beach, Laurie pleading with Amy, Jo denying Laurie, etc — but I think none is more emblematic of Gerwig’s directorial strengths and the film’s thematic goals than Christmas Day at the March’s. Set during the earlier timeline, all the girls still remain together at this point in time. Waiting for Marmee, they express their hopes and dreams for themselves, laying the groundwork for their ambitions in a subtle, but expressive way. Amy stands on the couch proclaiming she’ll be the best painter in the entire world, Jo commits to her intentions of writing while encouraging Meg’s acting interest, and Beth sits quietly with her musical ambitions, all the while their quick rapport signaling their strong relationships with one another and Gerwig’s acute awareness of natural language on screen.

When Marmee returns, she presents a decision for the girls: eat their extravagant Christmas breakfast or share it with the impoverished Hummel family. After a second a hesitation they are seen trudging through the snow and carrying out an empathetic act of kindness, a moment of simple humanity that embraces their good willed hearts and provides a compassionate texture to the Marches. But the scene’s finest moment comes with its punctuation.

As the girls put on their evening Christmas play for the neighbors, Marmee narrates a letter from their father away at war. Reading through, we learn of his hopes for each girl, wishing to return and find his little women of good virtue, kindness, and passion. All the while, Gerwig overlays images of the March sisters during said play — fake mustaches and fanciful attires in all — as a crowd of even younger girls look on in wonder, observing role models with wide eyed hopes that they too may grow up like them. The play continues, the audience sees an undeniable drive to do all things, and we understand that these girls will forge their own stories. A subtle notion, one that grows in prominence as the film progresses and brings the scene full circle to the morning, answering how the girls will accomplish their grand plans: on their own terms with persistence, compassion, and fearlessness.

-Greg Arietta

Knives Out

The Final Reveal

In an imaginative new take on the whodunnit structure, Rian Johnson sets up a maze of clues and reversals that culminates in an unpredictable reveal. After the twist half way through the film, the late Harlan Thrombey’s (Christopher Plummer) kind nurse Marta (Ana De Armas) is revealed to have accidentally injected him with the wrong medicine, leading him to stage a theatrical death to protect her from being found out by the shrewd Detective Blanc (Daniel Craig). This complete reversal of expectations takes us from craving the murderer to be caught to rooting for her to get away from it. It also builds sympathy for her as a character. Marta genuinely cares about Harlan far more than his actual family. He is the only one who treats her like a human being, while the rest can’t be bothered to even remember what country her family is from without making racial generalizations. We learn that she’s the only one with nothing to gain from his death, so it’s a just outcome for her to receive the entire Thrombey inheritance.

The final reveal scene follows the strategy laid out by Agatha Christie in her mystery novels. The family is brought together in the mansion (Rule 6. All suspects are gathered in one location) and Detective Blanc walks through the clues to bring everyone back up to speed (Rule 7. The detective explains what they have learned), but the missing piece of who hired Blanc is what brings it all together. As Marta’s ready to admit her guilt to the Thrombeys and recuse herself from the inheritance, Detective Blanc stops her, ridiculing the family as scheming vultures who treated Marta horribly (Rule 8. Comeuppance occurs, as the detective publicly embarrasses each suspect). Then Blanc launches into an even bigger reversal of expectations to reveal the true perpetrator of the crime: Ransom (Chris Evans).

As Blanc puts it, this donut mystery we thought was whole actually has a tinier hole in the center of our donut hole. It’s revealed that the aloof yuppie tampered with Marta’s medical supplies, causing Harlan’s death, and framing her so it would appear she overdosed the famed crime novelist. With his back against the wall and prison time a guarantee, Ransom attempts to extract one last murder by pulling a knife from Harlan’s knife throne and stabbing Martha with it. For a moment we believe her dead, but as they both stare each other in the face for a few brief moments, Ransom pulls the knife back to reveal it’s actually a retractable prop, completing Agatha’s ninth and final rule (Rule 9. The criminal is revealed, usually with a twist ending). This cathartic wrap-up exonerates Marta while proving that she is indeed a good person and Harlan’s death was truly and tragically a suicide. As a satisfying prestige to Rian Johnson’s cinematic magic trick, it manages to reconcile all of its elements without feeling like it’s holding the viewers’ hands.

It’s also worth mentioning the moment of Ransom stabbing Marta is a callback to the reveal of Pamela Vorhees in Friday the 13th, blue sweater and all.

-Megan Bernovich