Theo's Top Ten Films of 2020

“Is all this living really worth dying for?”

2020 was, frankly, an unbelievably shit year, even by the shoddy standards of the previous few. This last year I’ve needed movies more than ever, and I’ve also noticed a few interesting effects that 2020 has had on my film-watching habits – aside, that is, from the fact that I saw none of the movies on this list in a cinema.

As someone who has grown up in a culture simultaneously obsessed with and totally uninterested in the moving image, I’m accustomed to taking any mundane content within the filmic frame somewhat for granted – unless, of course, there is obvious reason not to do so. But with most of 2020 spent locked up indoors, I started relishing the little incidental bits of audio-visual information that graced my screen. I didn’t care all that much for the action taking place in Sofia Coppola’s On the Rocks, for example, but it was a total joy to spend 95 minutes exploring the streets of a city that wasn’t my own – hell, even just exploring an apartment that wasn’t my own.

At the same time, the dismaying responses to local and global political circumstances have only intensified my desire for a cinema that is both attentive to the realities of everyday life and critical of the various systems that govern our lives. I think the films I’ve designated as my top ten of this year reflect that – these are all films that balance some form of escapism with an imaginative engagement with the problems of the real world.

—

Honorable Mentions

David Byrne’s American Utopia (Spike Lee), Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution (Nicole Newnhman & James Lebrecht), Mangrove (Steve McQueen), Rocks (Sarah Gavron), Undine (Christian Petzold).

—

10. Beanpole

Beanpole is the only film on this list that I saw before coronavirus turned the world upside down – and, honestly, I’m not sure I would have even managed to finish it if I saw it a few months later. In this unsparingly bleak portrait of Leningrad at the end of the Second World War, we focus in on Iya (Viktoria Miroshnichenko), a nurse nicknamed “Beanpole” because of her unusually lofty stature. She suffers from catatonic seizures relating to trauma sustained during her service as an anti-aircraft gunner; without warning, she will freeze in place, letting out stuttered, guttural sounds. A tragedy relating to one of these episodes and the return of her friend Masha (Vasilisa Perelygina) from the Eastern Front set off disturbing events characterised by sexual manipulation.

Like Russian masterpieces Ivan’s Childhood or Come and See before it, Beanpole is both a showcase for impeccable filmmaking and an indispensable portrayal of wartime trauma. It certainly isn’t a ‘nice’ watch, if that’s what you’re looking for, but it is a strangely rewarding one. Remarkably, neither Miroshnichenko nor Perelygina have acted in a film before – their performances are easily among the best of the year, bringing an authenticity to a beguiling relationship that’s complexity is taken far beyond the lazy designation ‘toxic.’

You can read Cinema As We Know It’s review on the film here.

—

9. About Endlessness

About Endlessness, which might be Roy Anderson’s final film, is more of what we’ve come to expect from the Swedish director: a series of vignettes featuring drab, minimalist sets populated by pallid, nervous people failing – sometimes barely even trying – to connect with one another. One of its few narrative threads sees a Catholic priest experiencing a crisis of faith. “What should I do now that I’ve lost my faith?” the despairing man repeatedly begs his doctor. “I’m sorry, but I have to catch my bus,” the doctor replies and, aided by his secretary, slowly and inelegantly bundles the priest out of the door. The scene is typical of a film whose absurdity dares you to laugh even as the terrifying failures of compassion on show suggest that weeping would be a more appropriate response.

As with Anderson’s previous films, the spectres of fascism and imperialism haunt About Endlessness, sometimes in startlingly literal ways. This is a film full of comically ineffectual bystanders, and the filmmaker is particularly attentive to the role spectatorship and passivity play in human cruelty; that each vignette is captured in an extended take from a fixed camera starts to feel like our implication in exactly that. Despite all this, About Endlessness shouldn’t be mistaken for outright miserabilism. Quite the opposite – this is a deeply empathetic film that cries out for kindness and vitality. One scene in particular, which features three young women spontaneously breaking into dance outside a café, was easily one of the most joyous moments of film I’ve seen this last year.

—

8. Lovers Rock

While the other instalments of Steve McQueen’s Small Axe anthology series – which delves into the history of the West Indian community in London – feel like parts of a larger work, Lovers Rock stands alone as a truly singular piece of cinema. Set over the course of a single night at a Ladbroke Grove house party circa 1980, the film is “about” the tentative romance developing between Martha (Amarah-Jae St. Aubyn) and Franklyn (Micheal Ward). Really, though, McQueen is concerned with the details of the party itself – what people are wearing, who is flirting with who, the music – and the sensations they bring.

Tensions simmer away at the periphery: ritualistic courtship risks twisting into sexual violence, and the realities of Britain’s racial injustice are never totally pushed out of view. But for the most part, Lovers Rock is a celebration of the haven the house party affords, and the euphoria that one great night can bring. Coming towards the end of a year that will be remembered for its major Black Lives Matter protests, what a pleasure to see a film centred on Black joy. And in a year defined by separation and distance, by stasis and isolation, what a gift to be transported away to a crowded, sweaty dancefloor full of people singing, dancing, and tenderly holding each other.

You can read Cinema As We Know It’s review on the film here.

—

7. Dick Johnson is Dead

Reports of Dick Johnson’s death have been greatly exaggerated. At the beginning of this moving documentary Dick Johnson, filmmaker Kirsten Johnson’s beloved father, is seen alive and seemingly well. But Dick Johnson sure does die a lot in this movie. In one scene, an air conditioning unit falls on his head. In another, a careless workman manages to impale him with a plank. What’s really going on is less visually shocking but just as upsetting for a daughter to face up to: Dick Johnson is showing signs of dementia, the disease to which Kirsten lost her mother a decade previously. And so in Dick Johnson Is Dead the director decides to turn her father’s life into art by creatively staging hypothetical instances of his demise.

This proves to be a wildly rewarding filmmaking exercise – playful, imaginative, and unusually transparent aboutdocumentary practices and ethics. It helps that Dick Johnson is a wonderful subject worth spending time with. Above all else, I felt overwhelmed by the generosity on show here: from Dick, who is always willing to play along with his daughter’s experiment, and from Kirsten, who is able to transform her deepest anxieties into a film that allows us to work through our own.

—

6. Mank

David Fincher’s Mank – a title that should have carried an exclamation mark – is lively, flawed, and among the director’s best work. The film alternates between flashbacks of the screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) gallivanting through 1930s Hollywood and, in the film’s present day, a bed-bound Mankiewicz writing the screenplay for what would become Citizen Kane. No surprise that, upon its release, certain critics saw Mank as an attempt to revive the claim made by Pauline Kael in her controversial essay “Raising Kane” that it was Mankiewicz, not director Orson Welles, that should be recognised as the primary author of the film frequently touted as the greatest of all time.

Actually, the argument over the Kane writing credit – barely touched on here – distracts from the film’s real interest: the right-wing politics Mankiewicz discovers pervading America’s elite, and the role Hollywood plays in peddling it to the masses. And doesn’t that sound familiar? No doubt there’s plenty to enjoy here, from the razor-sharp dialogue to the playful, melancholic score to the captivating central performance given by Oldman. But Mank leaves a curiously bittersweet taste – its formal liveliness and dry humour offset by its protagonist’s profound disillusionment with that sinister relationship between politics and the media.

You can read Cinema As We Know It’s review on the film here.

—

5. The Kiosk

In The Kiosk guerrilla filmmaker Alexandra Pianelli documents her day-to-day life as a shopkeeper in the Parisian newspaper kiosk that has been in her family for four generations. The setting could hardly be smaller – the camera almost never leaves Pianelli’s perspective from behind her counter, a space which allows her just two paces. But through the director’s interaction with customers familiar and new, the film makes the thrilling suggestion that the whole world might enter into this kiosk. We get to know such diverse characters as Damien, a generous homeless man constantly losing his pet cat; Mariouch, who brings Alexandra baked goods and seems like a bit of a flirt; Christiane, an elderly woman who loves to talk; and Islam, a Bangladeshi fruit seller avoiding harassment by the French police.

Alongside this wonderful, Varda-esque portrait of a community, the film strikes a more mournful note: using cardboard models, Pianelli illustrates the decline of the printing industry in France and her business’ own precarious position as a result of it. What might we lose when we give up on print culture? Maybe, The Kiosk implies, in losing a space like this kiosk we miss out on unexpected opportunities for connections with the world.

—

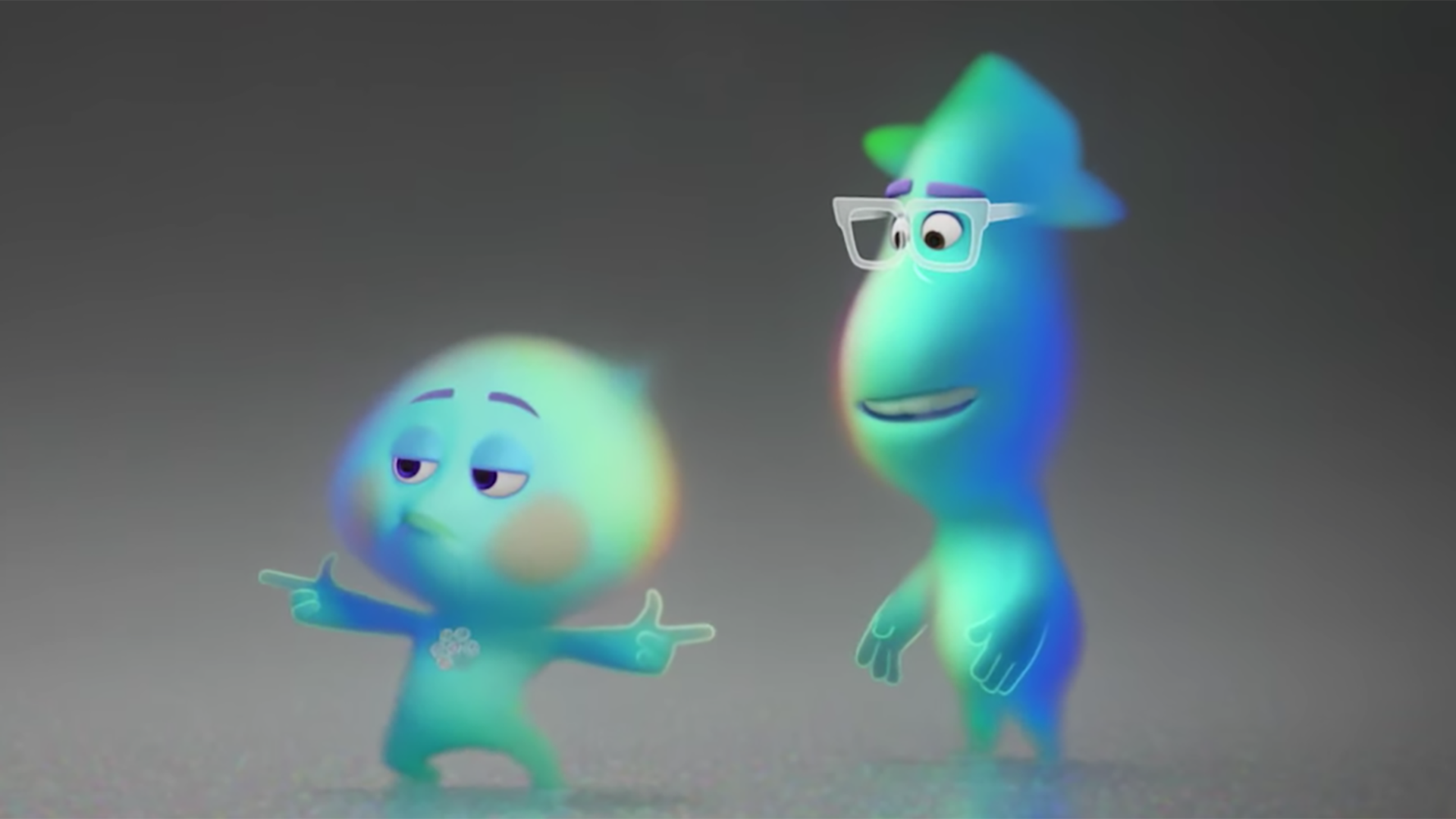

4. Soul

Here’s another film that celebrates finding connections with the world in unexpected places. Jamie Foxx voices Joe Gardner, a talented but unfulfilled jazz pianist stuck teaching an uninspired middle-school band. Just as it seems that Joe will finally get his big break – courtesy of an unexpected opportunity to play with celebrated saxophonist Dorothea Williams (Angela Bassett) – he falls down a manhole and dies. Refusing to accept his fate and move on to the great beyond, Joe makes it mission to get back to his Earthly body in time for the gig.

To say anything of how he goes about doing that would be to spoil the illimitable imagination injected into the film by writer-directors Pete Docter and Kemp Powers; suffice to say, Soul finds creative ways of visualising existential angst and tackling it head-on. It resists the usual glib messages associated with kids’ movies – be yourself! follow your dreams! – but neither does it take the equally lazy route of telling us to be thankful with what we’ve already got. Rather, Soul confronts in a startlingly head-on manner the inevitable disappointment that comes with fulfilling the passion we perceive as our soul’s purpose if we see it as our sole purpose.

You can read Cinema As We Know It’s review on the film here.

—

3. I’m Thinking of Ending Things

More existential angst! The plot of I’m Thinking of Ending Things seems fairly straightforward: a young woman (Jessie Buckley) who is considering breaking up with her boyfriend Jake (Jesse Plemons) drives to meet his parents, has dinner with them, and then drives home. This being a Charlie Kaufman film, however, it’s no surprise that that description proves woefully inadequate. Time and space are increasingly toyed with. Characters change clothes, change names, change voices, change age. At points, they even seem to change characters.

If all this, coupled with a knotty intertextuality and bleak subject matter, makes I’m Thinking of Ending Things a difficult watch, it also makes it one of the most stimulating and rewarding films in recent memory. I’d hesitate to call anything in this film comforting – a hilarious film-within-a-film interlude suggests the kind of rom-con catharsis Kaufman is railing against – but there’s something both reassuring and exhilarating about the shrewdness and honesty with which it confronts the insecurities we all face.

You can read Cinema As We Know It’s review on the film here.

—

2. Time

In 1999, when Sibil Fox Richardson (“Fox Rich”) and her husband, Robert, were in their early twenties, they tried – and failed – to rob a bank. Fox spent three years in prison, but Robert, whose lawyer advised him to reject a plea deal, was sentenced to sixty years without parole. Garrett Bradley’s stunning documentary Time combines years of home videos Fox recorded for him with recent footage of her determined efforts to overturn his life sentence. It helps that Richardson is as eloquent and impassioned a subject as a filmmaker could hope for: “What I clearly understood is that our prison system is nothing more than slavery. And I see myself as an abolitionist.”

In subject matter Time recalls another brilliant documentary: Ava DuVernay’s 13th, which also tackles mass incarceration and the legacy of Jim Crow. But Bradley’s film takes a completely different approach – a deeply intimate one, concerned less with the academic case against the injustice of the carceral state and more with the emotions of those on the outside. The title says it all. This is a film about time, a film that succeeds in giving an impression of what over twenty years of waiting feels like. That it manages to do so in under 80 minutes is nothing short of a miracle.

—

1. Kajillionaire

2020 was the year I was introduced to the work of Miranda July; in January, I watched her delightful debut Me and You and Everyone We Know, and in the height of UK lockdown in May saw and loved her moving follow-up The Future. Still, I wasn’t prepared for how much I’d adore Kajillionaire. July’s latest film follows Theresa and Robert Dyne (Debra Winger and Richard Jenkins), a small-time con artist couple, and their daughter Old Dolio (Evan Rachel Wood), who has essentially been raised for the sole purpose of aiding her parents’ scams. The trio are sheltered and mistrustful, and living in constant fear of a massive Los Angeles earthquake. Like July’s previous films, Kajillionaire is both humorous about and understanding of its characters’ flaws. It’s also characteristically brimming with surprising visual quirks – to skim on rent, the family live in a dilapidated office building next to a bubble factory, and one of the walls intermittently leaks sheets of fluffy pink foam.

July’s quirks shouldn’t be mistaken for shallow quirkiness; the lazy idea that her films are simply examples of twee hipsterism is reflective of the critical disservice July has been done by certain audiences. In all of her films, July’s interest in artifice, wackiness, and downright weirdness provides the necessary distance from which we can look at our own bizarre lives afresh. The masterstroke in Kajillionaire is inserting someone ‘normal’ into this world: Melanie (Gina Rodriguez), a bubbly but outwardly unremarkable young woman who is roped into the family’s scamming. Melanie forces Old Dolio to question everything she knows simply by offering her the warmth and curiosity her parents have denied her.

Kajillionaire is lots of things at once. It’s a cutting satire of the anxieties and absurdities of late capitalism, and a showcase for hilarious performances from all the actors involved. In its portrayal of parents who shelter and brainwash their child to suit their own narrow worldview, it’s also an amusingly dark evaluation of all familial relationships. But above all else, Kajillionaire is a sincerely felt portrait of a woman belatedly coming into her own, discovering love – and life – for the first time.

As I’ve been writing this list, it’s dawned on me that all of my selections – with one Steve McQueen-shaped exception – are somewhat morbid films. There’s the death-defying shenanigans of Dick Johnson and Soul, the wartime suffering of Beanpole and About Endlessness, the personal tragedies that punctuate Mank and The Kiosk, the dark double meaning of the title I’m Thinking of Ending Things, and Time’s revelation that a life sentence is also a kind of death sentence. Two pivotal scenes in Kajillionaire are similarly inclined. In the first, Old Dolio’s family attempt to rob the house of an elderly man they then discover is dying; “Life is nothing,” she tells the man, “It’s not that big of a deal.” But by the later scene, when the dreaded earthquake finally hits, Old Dolio experiences a joyous kind of rebirth. Death has certainly been on my mind this miserable year even more than usual, though it’s disturbing how quickly I became desensitised to seeing a rolling death count on the news every night. Cinema has been a way of making those stats seem less abstract – and all of these films use death to ponder the question of what makes life worth living. That they all come up with such wildly different answers is one reason I’ll keep coming back for more.

—