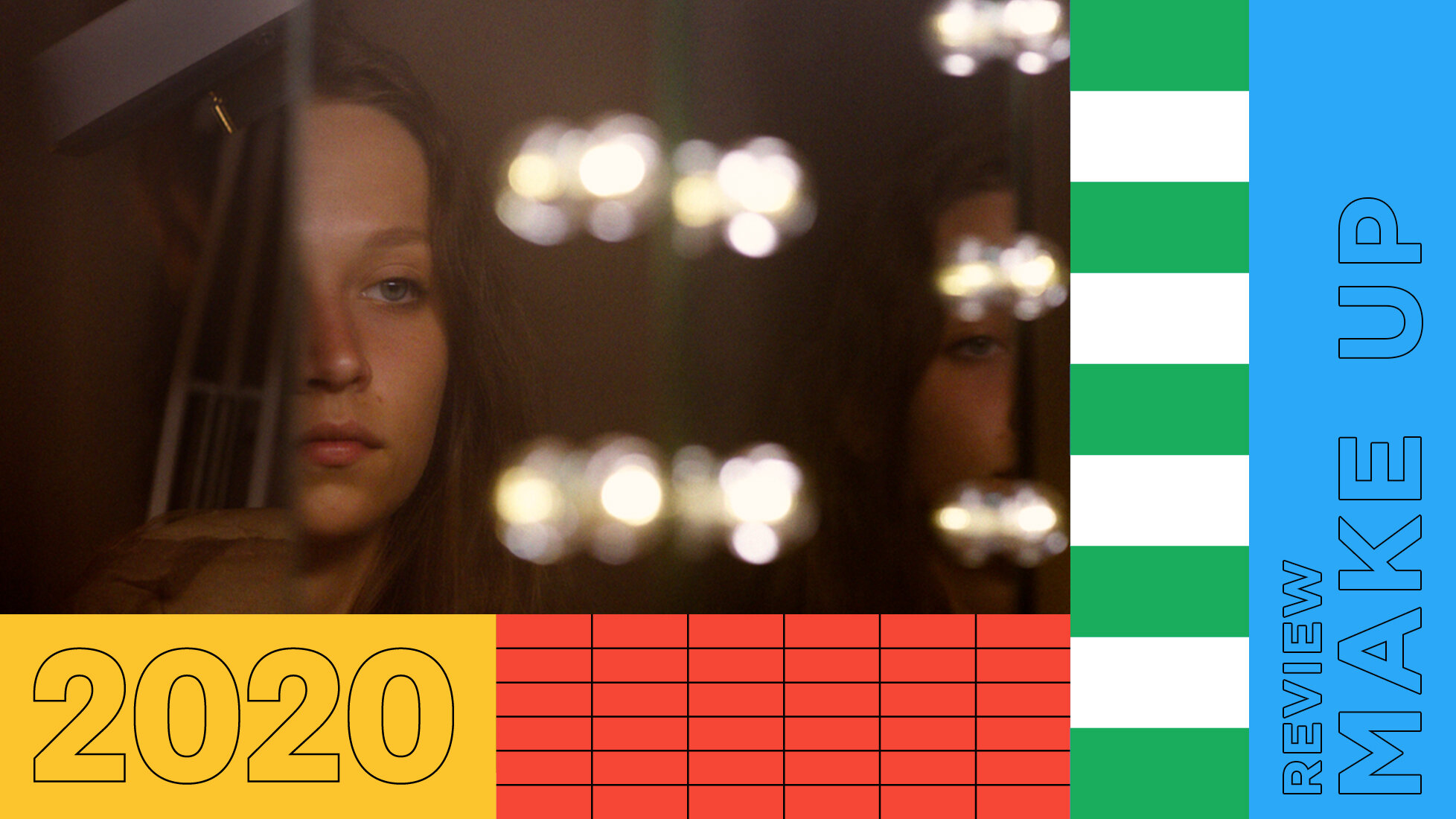

SXSW Review: ‘Make Up’ Descends Into the Psychological Turmoil of Infidelity and Self Discovery

“The sea is a great healer.”

The inescapable thought of your lover’s infidelity is a plague on the mind. Fueled by jealousy and suspicion, it can be difficult to come out from under the idea if evidence piles up and irregular behavior supports the claim. So desperately do you want to know the truth, but afraid to make the accusation, that you’ll let nightmarish scenarios fill your head until you can’t take it anymore. In Make Up, Claire Oakley takes this idea and turns it into a surreal haunting mystery where an all consuming obsession leads to an unlikely discovery.

Ruth (Molly Windsor) travels to a remote seaside campsite where her boyfriend Tom (Joseph Quinn) works for the summer. After a period of long distance, the two are reunited to much elation, but when Ruth discovers a lipstick stain on Tom’s mirror followed by strands of long red hair on his clothes, she begins to suspect he cheated on her. With each passing day, she avoids confrontation, and a festering obsession builds to find out if he cheated and with who.

The film’s title is indicative of the primary mechanics and metaphors at play in Make Up. Not only is make up the first piece of evidence that Ruth discovers, but Ruth also herself wears a layer of metaphorical make up. As she descends into this pit of psychological turmoil, she makes a discovery about herself, one only brought about by conflict in her three year long relationship. But more astutely with regards to the events of the film, Ruth makes up scenarios in her head about Tom. As the narrative progresses, seeds of doubt sow themselves in here mind. Fleeting jump cuts to acts of infidelity are repeated, and moments of dreamlike hallucination grow in severity as her obsession with the ever increasing reality she dreads becomes all consuming.

More impressively is how Make Up can transition in and out of these moments of psychological surrealism without whiplash. Ruth’s suspicions manifest themselves in scenes of psychological horror, taking on a thriller-like quality to them. To paint a picture, there is a moment where Ruth showers in the communal bathroom and begins to hear sex noises in the adjacent stall. She speculates if the couple copulating on the other side of the wall involves Tom, and she starts to project her fears onto it. But this moment isn’t limited to one scene. The incident reoccurs later on with changed details and different perspective from Ruth. It’s a shifting recollection that calls into question the reality of the situation at hand and whether Ruth’s suspicions are valid or compulsive. It is no small feat that these moments of nightmarish thinking are conveyed with as much clarity as they do, but I would say it is a testament to Oakley’s direction, one that navigates a difficult narrative proposition with steadfast vision, that it succeeds. A truly impressive act from a first time feature film director.

Then there is the discovery. Without spoiling the reveal, there is moment where the film makes its jump, going from the ephemeral to the concrete and solidifying the narrative questions proposed. Scenes that posed speculation are given answers, even if only emotionally and not literally. It is here where a moment of self realization takes hold, and an aching poeticism emerges from Ruth’s journey. For much of the narrative she is haunted, tortured by a reality she didn’t want to be true, but by the time we reach the end, there is reprieve and release waiting that feels honest, and for the first time in the film, we know the truth.

—